What is Technocracy?

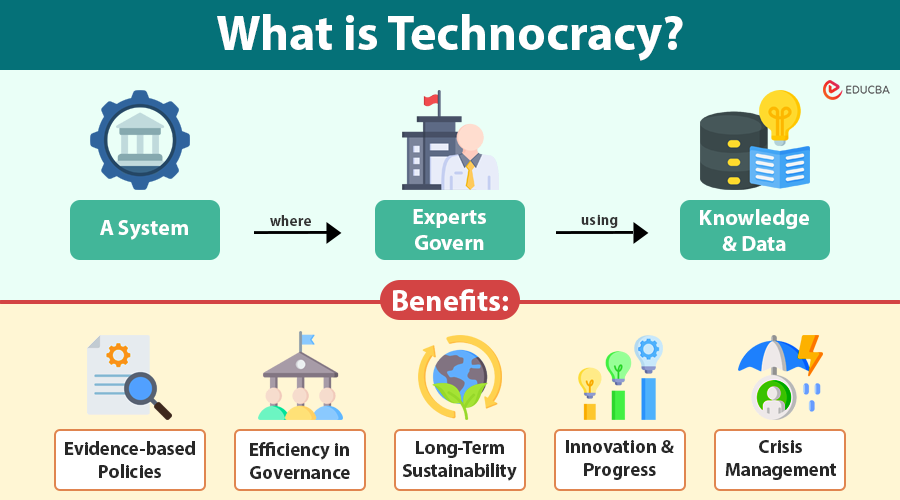

Technocracy is a system of governance in which experts and specialists, rather than elected politicians, make decisions based on knowledge, data, and technical expertise.

Unlike democracy, which relies on elections and representation, technocracy aims to remove subjective politics from governance, replacing it with rational, evidence-based solutions.

Core Features:

- Leadership based on expertise rather than political popularity.

- Emphasis on scientific methods and measurable outcomes.

- Technocrats view governance as a technical problem-solving exercise.

- It measures economic value by efficiency and productivity, rather than solely by monetary gain.

This vision treats society as a machine and engineers it for maximum efficiency, sustainability, and fairness.

Table of Contents

- Meaning

- Historical Origins

- Key Principles

- Technocracy vs. Democracy vs. Meritocracy

- Advantages

- Disadvantages and Criticisms

- Examples

- Technocracy in the Modern Era

- Future of Technocracy

Historical Origins of Technocracy

The roots stretch back over a century, though its underlying principles are even older.

Early Foundations

- Industrial Revolution: As machines and industry transformed economies in the 18th–19th centuries, intellectuals began questioning whether governance should adapt to technical complexity.

- Frederick Taylor & Scientific Management: In the early 20th century, Taylor’s “scientific management” revolutionized productivity in factories and laid the groundwork for applying engineering logic to social systems.

The 1930s Technocracy Movement in the U.S.

- During the Great Depression, political leaders struggled to stabilize economies. Disillusionment with capitalism and democracy opened space for alternative ideas.

- Howard Scott and the Technocracy Inc. movement argued that engineers could design a more rational economic system.

- They proposed replacing the price-based economy with an “energy accounting” system that measured production and consumption in energy units, rather than in monetary terms.

Global Influence

- USSR and China: While not purely technocratic, elements of central planning reflected technocratic logic.

- Mid-20th Century: Post-war reconstruction in Europe saw a heavy reliance on economists and engineers to rebuild infrastructure, hinting at a technocratic governance approach.

- Modern Globalization: Today, technocratic principles shape institutions like the IMF, World Bank, and central banks, where unelected experts influence policies worldwide.

Key Principles of Technocracy

Technocracy rests on guiding principles that distinguish it from other governance systems:

- Rule of experts: Decision-making power lies with subject-matter experts, not career politicians. For instance, doctors design healthcare systems, economists craft financial policies, and engineers plan infrastructure.

- Scientific method: Governments test, measure, and refine policies like experiments. Instead of ideology, data, research, and peer-reviewed findings form the foundation of governance.

- Efficiency & optimization: The system aims to minimize waste and maximize output, whether in terms of energy, resources, or administrative processes.

- Long-term planning: Politicians often think in terms of short election cycles, but technocracy emphasizes strategic foresight planning for decades to achieve long-term sustainability.

- Depoliticization of governance: Strips governance of rhetoric and partisanship, aiming for neutral, rational decision-making.

Technocracy vs. Democracy vs. Meritocracy

Technocracy is often confused with related systems, but the differences are crucial:

| Feature | Technocracy | Democracy | Meritocracy |

| Basis of Power | Technical knowledge and expertise | Popular vote and representation | Talent, skill, or achievement |

| Decision-Makers | Scientists, engineers, economists, experts | Elected politicians representing citizens | Individuals selected based on merit (education, performance, etc.) |

| Primary Goal | Efficiency, rational problem-solving, long-term sustainability | Representation, equality, and freedom of choice | Rewarding and promoting capable individuals |

| Strengths | Evidence-based policies, efficiency, innovation | Inclusiveness, legitimacy, accountability | Promotes excellence and competence |

| Weaknesses | Risk of elitism, lack of accountability, reduced participation | Susceptible to populism, short-term focus, political gridlock | May overlook fairness and social equality |

| Examples | Central banks, Singapore’s governance, China’s leadership model | India, USA, UK, most modern nations | Corporate promotions, academic selection, competitive bureaucracies |

Advantages of Technocracy

Supporters highlight many benefits:

- Evidence-based policies: Removes guesswork and ideology by relying on proven scientific and technical solutions.

- Efficiency in governance: Streamlines decision-making and resource management, reducing bureaucracy and corruption.

- Long-term sustainability: Allows for strategic planning in fields like energy, infrastructure, and climate change mitigation.

- Innovation & progress: Encourages rapid adoption of new technologies in governance and society.

- Crisis management: Experts are often better equipped to handle crises, such as pandemics or financial collapses, by offering data-backed solutions quickly.

Disadvantages and Criticisms of Technocracy

Despite its appeal, it is not without drawbacks:

- Democratic deficit: Weakens representation and public participation in governance.

- Elitism and exclusion: Concentrates power among highly educated elites, marginalizing ordinary citizens.

- Value blindness: Not all issues are technical; cultural, ethical, and moral values often resist purely scientific solutions.

- Accountability problems: Experts may lack direct responsibility to the public, resulting in a transparency gap.

- Over-reliance on technology: Risks reducing society to numbers and algorithms, ignoring human complexities.

Examples of Technocracy in Practice

No nation practices pure technocracy, but many nations incorporate its elements globally:

- Singapore: Known for data-driven governance, technocratic leadership, and high efficiency in urban planning, healthcare, and education.

- European Union (EU): Critics argue that institutions like the European Central Bank embody technocracy, since unelected officials wield significant power over member states.

- China: Leadership often has engineering or scientific backgrounds, blending authoritarianism with technocratic elements.

- Central Banks Worldwide: Independent central banks, such as the U.S. Federal Reserve, are classic examples of technocratic governance in economic policy.

- COVID-19 Pandemic Response: Many nations temporarily shifted toward technocracy by letting epidemiologists and healthcare experts lead public policy.

Technocracy in the Modern Era

The 21st century has made it increasingly relevant:

- Climate change: Requires policies rooted in environmental science and engineering.

- Artificial intelligence & big data: Enables data-driven governance, where algorithms support decision-making.

- Healthcare systems: Technocratic frameworks guide pandemic response, vaccine distribution, and health economics.

- Digital transformation: Governments rely on IT experts to shape cybersecurity, privacy laws, and digital infrastructure.

However, it also faces resistance as people demand more democratic accountability in a world dominated by experts and algorithms. The balance between public voice and expert authority remains a contested issue.

Future of Technocracy

The future will probably move toward hybrid systems that mix democracy with technocracy:

- Technocratic-democratic systems: Citizens continue electing leaders, but experts guide technical decisions (e.g., in energy or healthcare).

- AI-augmented governance: Artificial intelligence may support experts in crafting policies with predictive models.

- Participatory technocracy: Citizens provide input through digital platforms, while experts design and implement policies.

- Global governance: As global problems transcend borders, technocratic institutions (like climate councils or pandemic task forces) may play bigger roles.

Ultimately, the challenge is to harness expertise without eroding public trust and democratic values.

Final Thoughts

Technocracy represents a vision of governance led by science, rationality, and expertise. It promises efficiency and innovation but also raises concerns about elitism, accountability, and democracy. In the world of complex global challenges, it is not just a theoretical model; it already shapes institutions, policies, and crisis responses.

The debate is not about whether technocracy will influence governance, but how societies can balance expert-driven decision-making with democratic legitimacy. The future may not belong entirely to technocracy, but elements of it are becoming increasingly unavoidable.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQ)

Q1. What is the main idea of technocracy?

Answer: Technocracy is the belief that experts and specialists should govern society, using data, science, and technical knowledge to guide decision-making instead of politics.

Q2. Has technocracy ever been fully implemented?

Answer: No country has ever been a pure technocracy; however, elements of technocracy exist in places like Singapore, China, and independent central banks worldwide.

Q3. Is technocracy better than democracy?

Answer: It depends on the context. Technocracy ensures efficiency and rational decisions, while democracy guarantees representation and public accountability. A hybrid of both may be more practical.

Q4. What are the dangers of technocracy?

Answer: The primary dangers include elitism, loss of democratic control, reduced accountability, and an overreliance on technology to address complex social problems.

Q5. Will AI make technocracy more common?

Answer: Yes, artificial intelligence can strengthen technocracy by supporting data-driven governance, but it also creates new concerns about transparency, fairness, and human oversight.

Recommended Articles

Explore related articles on governance, democracy, and the role of technology in shaping societies to gain a deeper understanding of politics and economics.