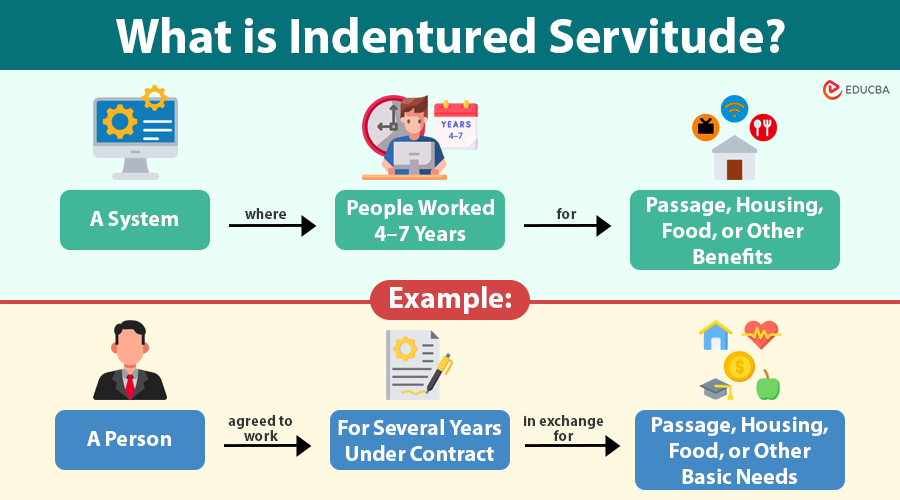

Introduction to Indentured Servitude

Indentured servitude was a system where people agreed to work for about four to seven years in return for passage, housing, food, or other benefits. This system was prominent from the 16th through the 19th centuries and served as a cornerstone of colonial economies in the Americas, the Caribbean, and Asia.

Though often distinguished from slavery because it was temporary and contractual, indentured servitude was still highly exploitative. Many laborers endured brutal working conditions, corporal punishment, and high mortality rates, while only a fraction successfully transitioned to independent livelihoods afterward. Understanding this system provides insight into global labor exploitation, migration patterns, and the economic foundations of colonial societies.

Origins of Indentured Servitude

Indentured servitude began in medieval Europe, where people often worked for others to pay off debts or meet obligations. With the rise of European colonialism in the 16th century, this practice evolved into a transatlantic labor system.

- Economic push factors: Europe faced significant poverty, unemployment, famine, and social upheaval. Wars like the English Civil War displaced thousands, while enclosure movements in England deprived peasants of land. Many low-income families saw indenture as their only path to opportunity abroad.

- Colonial pull factors: Colonies in the Americas and Caribbean faced severe labor shortages. Native populations had greatly declined due to disease and conquest, and European settlers by themselves could not meet the growing need for farm labor.

- State and private interests: Governments, shipping companies, and colonial landowners all encouraged indentured labor. For elites, it was a way to populate colonies with cheap labor, while for ordinary people, it offered a slim hope of land ownership or upward mobility.

Thus, indentured servitude emerged as a “middle ground” between free labor and slavery, though in practice, it often leaned closer to coercion.

How the System Worked?

Contracts governed indentured servitude, though the enforcement of rights varied widely across colonies.

- Recruitment and coercion: Some individuals willingly signed indentures, motivated by the promise of land or wages after service. Others, especially children, and women, were deceived or forcibly taken. “Spirits” (recruiting agents) were notorious for kidnapping or tricking people in ports and taverns.

- Contracts: Contracts were legally binding, often notarized, and specified the length of service, duties, and provisions. Some contracts included “freedom dues,” such as clothing, money, tools, or land grants at the end of service. However, these promises were frequently unfulfilled.

- Living and working conditions: Servants endured long hours of agricultural labor, often under harsh masters. Housing was basic, food was scarce, and medical care was minimal. Masters beat, locked up, or forced servants to serve longer if they disobeyed or tried to escape.

- Completion of service: At the end of service, many indentured servants found themselves destitute, as land was increasingly scarce and “freedom dues” were inconsistently delivered. Others became tenant farmers, wage laborers, or migrated further westward in search of opportunity.

Indentured Servitude in Colonial America

Indentured servitude was critical to the early development of North America, particularly in the 17th century.

- Chesapeake colonies: Virginia and Maryland’s booming tobacco economy relied heavily on indentured labor. Tobacco was labor-intensive, requiring planting, weeding, harvesting, and curing. Colonists imported thousands of indentured Europeans to meet demand.

- Demographics: Between 1607 and 1700, roughly two-thirds of European migrants to the American colonies arrived as indentured servants. Most were young, single men, though women and children were also part of the system. Many were from rural England, Ireland, and later Germany.

- Mortality and hardship: Conditions in the Chesapeake were deadly. Disease, poor sanitation, and overwork led to death rates as high as 40%. Servants often did not survive long enough to complete their contracts.

- Transition to slavery: As African slavery became more economically advantageous, landowners shifted away from indentured Europeans. Slaveholders enslaved Africans for life, passed slavery on to their children, and controlled them more tightly. By the 18th century, African slavery had largely replaced indentured servitude in the southern colonies.

Indentured Servitude in the Caribbean and Beyond

While indentured servitude in America is well-known, the system also expanded across the Caribbean, Africa, and Asia.

- Caribbean Plantations: Sugar plantations required massive labor forces. At first, Europeans worked as indentured servants, but many died quickly from tropical diseases and harsh conditions, even more than in North America. By the late 17th century, enslaved Africans became the dominant labor source, though indentured systems continued alongside slavery.

- Indian Indenture System (1834–1917): After Britain abolished slavery, planters in colonies such as Trinidad, Guyana, Mauritius, Fiji, and South Africa turned to India for indentured workers. Over 1.3 million Indians migrated under contract, often lured by false promises. They faced grueling work, cultural dislocation, and strict colonial controls, though some later established permanent communities.

- Chinese Indenture (“Coolie Labor” ): At first, Europeans worked as indentured servants, but many died quickly from tropical diseases and harsh conditions, even more than in North America. Many endured near-slavery conditions in plantations, mines, and railroads. Contracts were exploitative, with high rates of abuse and mortality.

These global movements left lasting legacies: Indo-Caribbean, Sino-Caribbean, and Indo-African communities that continue to shape cultural and political life in former colonies.

Comparison to Slavery

Though often presented as distinct, indentured servitude shared many similarities with slavery:

Similarities:

- Harsh physical labor, especially in agriculture and plantations.

- Severe punishments for disobedience or escape attempts.

- Loss of autonomy, with masters exercising near-total control over servants’ daily lives.

Differences:

- Duration: Contracts were temporary, usually 4–7 years.

- Legal rights: Servants could, in theory, appeal to courts, though justice was rarely on their side.

- Inheritance: Servitude did not pass to children, unlike slavery.

- Freedom: Completion of service allowed legal independence, though economic opportunities were limited.

Despite these differences, many contemporaries saw indentured servitude as “slavery by another name,” especially in colonies where abuses were rampant.

Decline of Indentured Servitude

The system gradually faded for several reasons:

- Economic shift: In North America, enslaved Africans provided a cheaper, more permanent labor force.

- Rising wages in Europe: As living standards improved, fewer Europeans were willing to indenture themselves.

- Humanitarian criticism: Reformers highlighted abuses, especially in the Indian indenture system, drawing parallels to slavery. Activists, missionaries, and politicians lobbied against it.

- Legal reforms: Britain officially abolished the Indian indenture system in 1917. Other colonial powers followed suit, ending contract labor systems globally.

Legacy and Impact

Indentured servitude left a profound impact that continues to shape societies today:

- Migration and diaspora: It triggered one of the largest waves of global migration before the modern era. Indo-Caribbean and Sino-Caribbean communities are direct results of indenture.

- Cultural blending: Music, religion, cuisine, and language in the Caribbean, Fiji, Mauritius, and Africa bear the imprint of Indian and Chinese indentured workers.

- Economic development: Colonies depended on indentured labor to build infrastructure, cultivate plantations, and sustain commerce.

- Labor rights movement: The documented abuses of indentured systems laid the groundwork for early labor reforms, setting precedents for modern workers’ protections.

- Historical memory: Many societies remember indentured servitude both as a story of survival and resilience and as a painful time of exploitation.

Final Thoughts

Indentured servitude was a labor system born out of global economic needs, colonial expansion, and social inequality. It promised opportunity but often delivered exploitation and hardship. Though it differed from slavery in legal terms, many laborers endured conditions just as brutal.

Its legacy endures today in the migration patterns, cultural identities, and labor movements shaped by those who lived through it. Studying indentured servitude reminds us that the global economy has long depended on vulnerable workers, and that the struggle for dignity and justice in labor is as old as colonial history itself.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1. Could indentured servants marry or have families during their service?

Answer: In most colonies, servants needed their master’s permission to marry. Having children could complicate contracts, and in some cases, female servants who became pregnant had their service extended to cover lost labor time.

Q2. Were women commonly indentured servants?

Answer: Yes, though fewer women than men entered indenture. Women often worked in households as domestic servants, cooks, or nurses. They were more vulnerable to exploitation, including sexual abuse by masters, and had fewer options for independence after their contracts ended.

Q3. Did indentured servitude exist outside of the colonial period?

Answer: Yes. Variations of indentured contracts have existed in many societies. For example, apprenticeships in medieval Europe shared similarities, and modern forms of bonded labor in parts of Asia echo aspects of indentured servitude.

Q4. Are there modern forms of indentured servitude?

Answer: While traditional indenture has ended, forms of debt bondage, human trafficking, and exploitative migrant labor systems still exist today. These modern practices resemble indentured servitude because unfair contracts often tie workers to their employers.

Recommended Articles

We hope this guide on Indentured Servitude was helpful. Explore related articles on labor systems, migration history, and colonial economies to deepen your understanding of global workforce dynamics.