What is the Peter Principle?

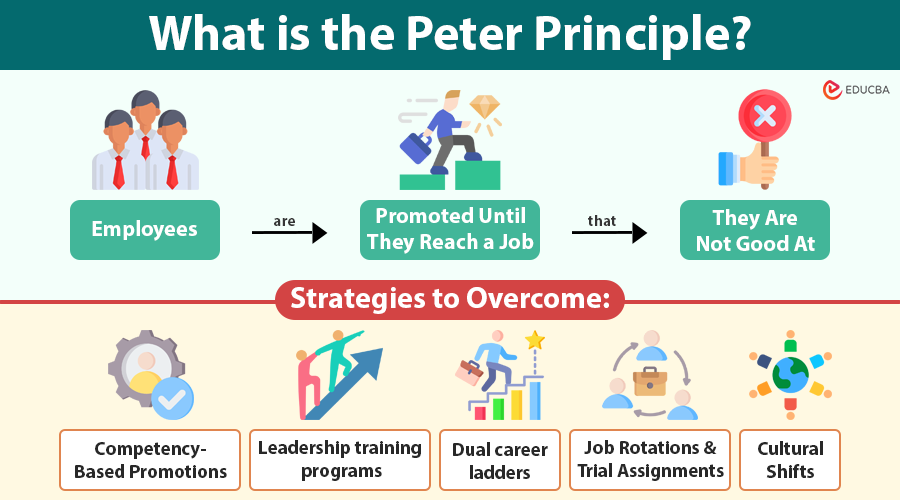

The Peter Principle is the concept that in a hierarchy, employees are promoted based on their success in previous roles until they reach a position where they are no longer competent.

Example of Peter Principle:

- An organization may promote a teacher who excels at teaching to a principal, but the teacher’s strengths may not align with administrative work, budgeting, and policy implementation.

- An organization might promote a skilled surgeon to hospital director, but the surgeon may fail to handle staff disputes, finances, or logistics.

This principle emphasizes that skill sets are often non-transferable across levels of hierarchy. Technical brilliance in one role does not automatically translate into managerial or strategic competence in another.

Table of Contents

- What is the Peter Principle?

- Origins and Background

- Key Mechanisms of the Peter Principle

- Real-World Examples

- Psychological and Organizational Impacts

- Criticism and Limitations of the Peter Principle

- Strategies to Overcome the Peter Principle

- Modern Relevance of the Peter Principle

Origins and Background

Dr. Laurence J. Peter, a Canadian educator and management theorist, observed bureaucratic inefficiencies while studying educational systems and organizations in the mid-20th century. He compiled his findings in his 1969 satirical yet insightful book The Peter Principle: Why Things Always Go Wrong.

- The book became a bestseller, resonating with readers because it humorously yet accurately captured workplace frustrations.

- Though written with a touch of satire, the principle gained traction in serious management discussions.

- Peter’s collaborator, Raymond Hull, helped shape the book’s accessible style, making the theory widely known beyond academia.

The principle also aligns with broader theories of bureaucracy, particularly those discussed by Max Weber and later thinkers, who highlighted inefficiencies inherent in rigid hierarchical systems.

Key Mechanisms of the Peter Principle

1. Promotion Based on Current Performance

Organizations often promote employees based solely on their performance in their current role. While logical on the surface, this ignores the fact that higher-level jobs usually require different competencies.

2. Skill Misalignment

A person who thrives in analytical problem-solving may not automatically excel in people management. The assumption that success in one domain predicts success in another creates misalignment.

3. Cumulative Incompetence

Organizations build layers of ineffective managers when they keep promoting employees beyond their competence. The higher this chain goes, the more it affects decision-making and organizational outcomes.

4. Cultural Reinforcement

Many cultures view promotions as the ultimate recognition of success. This mindset discourages organizations from considering alternative career paths (e.g., specialist tracks), pushing employees into roles they are unsuited for.

Real-World Examples

- Corporate environments: Tech companies often promote highly skilled programmers to managerial roles. Many lack the leadership and interpersonal skills required to guide teams, resulting in lower morale and productivity.

- Government bureaucracies: Seniority-based promotions in government services frequently elevate employees regardless of leadership capability, leading to inefficiency and “red tape.”

- Military structures: Some armed forces promote outstanding soldiers to officer ranks where strategic thinking is required, but battlefield skills alone do not guarantee success.

- Sports: Organizations often promote former star players to coaching roles. While they understand the game deeply, not all can translate personal skill into team management and motivation.

These examples show that the principle is not restricted to one sector but manifests across industries, professions, and cultures.

Psychological and Organizational Impacts

- Employee frustration and burnout: Employees promoted beyond their competence may feel inadequate and overburdened, leading to stress, anxiety, and reduced job satisfaction.

- Decline in team morale: Teams led by incompetent managers often feel neglected, undervalued, or micromanaged. Talented employees may leave, worsening attrition rates.

- Stifled innovation and creativity: Ineffective leadership tends to discourage experimentation and risk-taking, which are critical for growth. Employees become disengaged, sticking only to the minimum requirements.

- Wasted resources: Promotions that result in incompetence lead to costly mistakes, poor project execution, and reduced efficiency. Training and rehiring add to the financial burden.

- Cultural impact: If incompetence spreads across layers of management, it creates a culture where mediocrity becomes the norm and true meritocracy is lost.

Criticism and Limitations of the Peter Principle

- Not universally applicable: Not all promotions lead to incompetence. Many individuals adapt well to higher responsibilities.

- Learning and growth: Employees often acquire new skills through training, mentorship, and experience, enabling them to succeed in advanced roles.

- Improved HR practices: Modern organizations use psychometric testing, 360-degree evaluations, and leadership assessments to reduce misaligned promotions.

- Satirical origin: Since the principle was originally satirical, some critics argue it oversimplifies the complexities of organizational dynamics.

Despite these criticisms, the principle remains a useful lens through which to examine workplace inefficiencies.

Strategies to Overcome the Peter Principle

- Competency-based promotions: Promotions should consider the skills required for the next role rather than past performance alone.

- Leadership training programs: Preparing employees with management and soft-skills training can bridge the gap between technical ability and leadership requirements.

- Dual career ladders: Organizations can create career paths where employees gain recognition and compensation as specialists without being forced into managerial roles. For example, “principal engineer” or “distinguished scientist” roles in tech and research.

- Job rotations and trial assignments: Allowing employees to experience leadership tasks before full promotion helps gauge readiness and interest.

- Mentorship and coaching: Senior leaders can mentor rising talent, offering guidance and feedback to ensure smoother transitions.

- Cultural shifts: Recognizing that promotions are not the only measure of success encourages employees to pursue roles aligned with their strengths.

Modern Relevance of the Peter Principle

In the 21st century, organizations face challenges such as rapid technological change, globalization, and remote work. The Peter Principle remains relevant because:

- Flatter hierarchies: While modern firms reduce layers of management, the risk of misaligned promotions still exists.

- Remote work: Leadership now demands digital communication, empathy, and adaptability—skills that may not be present in technically strong employees.

- Talent retention: Poor management remains a top reason for employee turnover, directly linking the principle to real-world business costs.

- Agile and dynamic workplaces: Adaptability and emotional intelligence matter more than ever, and promoting solely on technical merit can harm organizational resilience.

Final Thoughts

The Peter Principle highlights a fundamental flaw in organizational hierarchies: leaders often award promotions for past performance rather than future potential. Although Dr. Peter introduced the principle humorously, it exposes a serious issue that affects productivity, morale, and leadership effectiveness.

Organizations that ignore this principle risk building layers of ineffective management that erode efficiency and innovation. However, by adopting competency-based promotions, leadership training, and alternative career paths, companies can counter its effects. Ultimately, organizations face the challenge of not only rewarding competence but also ensuring that employees are prepared, trained, and truly suited for the responsibilities ahead.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1. Is the Peter Principle still relevant today?

Yes, modern organizations keep the Peter Principle relevant because they often promote employees based on current performance rather than future potential, especially in fast-changing workplaces.

Q2. How is the Peter Principle different from the Dilbert Principle?

The Dilbert Principle, coined by cartoonist Scott Adams, suggests that companies intentionally promote incompetent employees to management to minimize the damage they can do in other roles. The Peter Principle, on the other hand, highlights unintentional promotion to incompetence.

Q3. Can the Peter Principle be avoided completely?

It is difficult to avoid entirely, but organizations can minimize it through competency-based promotions, leadership development programs, dual career ladders, and effective mentorship.

Q4. How does the Peter Principle impact organizational success?

When many leaders operate at their level of incompetence, decision-making suffers, innovation slows, employee turnover increases, and overall efficiency declines.

Q5. Why is the Peter Principle considered humorous as well as serious?

Although introduced in a satirical book, the principle reflects real workplace dynamics, which makes it both humorous in its irony and serious in its implications for leadership and management.

Recommended Articles

We hope this guide on the Peter Principle was helpful. Explore related articles on leadership strategies, employee motivation, and organizational behavior to better understand workplace dynamics.