What is Moral Hazard?

Moral Hazard is when a person, business, or organization takes more risks because they do not have to face the full consequences of their actions.

For example, a driver with full car insurance might drive carelessly, assuming that the insurer will pay for damages. On a larger scale, a bank might issue risky loans if it expects a government bailout during crises.

It is not just an abstract theory, but has been central to debates around financial crises, healthcare systems, welfare policies, and corporate behavior. Understanding it helps policymakers, businesses, and individuals design better systems to encourage responsibility and minimize excessive risk-taking.

Table of Contents

- Meaning

- Origin and History

- Key Features

- Types

- Causes

- Moral Hazard in Different Sectors

- Moral Hazard in Economics

- Moral Hazard in Game Theory

- Impact

- Real-Life Case Studies

- Criticism

- Solutions

Origin and History of Moral Hazard

The idea of moral hazard has deep historical roots.

- 17th Century Insurance Markets: Early insurers noticed that policyholders became less cautious once they were covered. For instance, fire insurance sometimes led to property owners neglecting fire safety.

- Adam Smith (1776): In The Wealth of Nations, Smith said people take risks if they do not suffer the full results.

- 19th Century Economics: The phrase “moral hazard” became common in insurance contracts.

- Kenneth Arrow (1963): The Nobel laureate formalized the concept in modern economic theory, particularly in healthcare, where patients might overuse medical services if costs are covered.

- Modern Usage: Today, moral hazard is applied far beyond insurance. It is a central concept in banking regulation, financial crises, government policy, and corporate governance.

Key Features of Moral Hazard

Moral hazard has certain defining characteristics:

| Feature | Definition | Example |

| Asymmetry of Risk and Reward | One party enjoys the benefits of risky behavior while another bears the costs. | A CEO may pursue high-risk investments because shareholders absorb any losses. |

| Hidden or Unobservable Behavior | Risky actions often cannot be fully monitored. | A borrower may misuse loan funds without the lender’s knowledge. |

| Incentive Distortion | When risks are shifted, incentives to act responsibly weaken. | Full insurance coverage without deductibles encourages reckless use of resources. |

| Occurs Post-Agreement | It happens after an agreement, unlike adverse selection, which occurs before. | Employees may take more risks after being given full job security. |

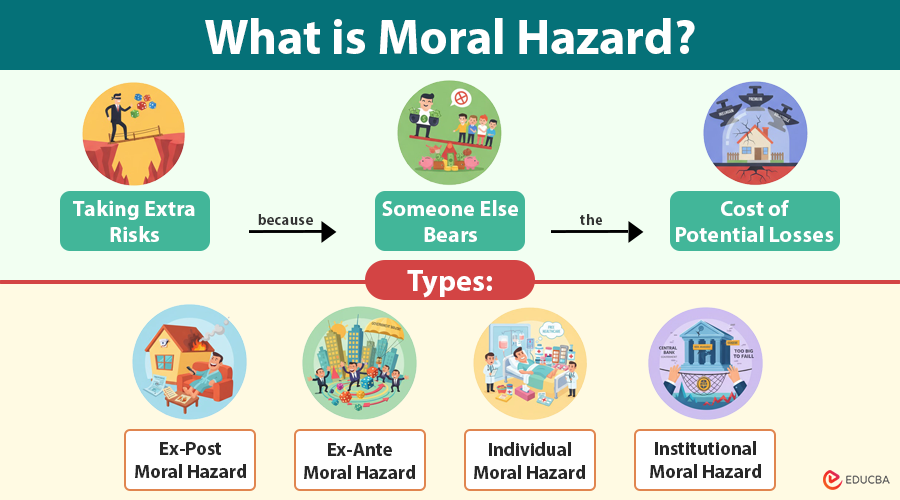

Types of Moral Hazard

Moral hazard happens when individuals or organizations take risks without facing the full results of their actions. It manifests in different ways depending on timing, scale, and the actors involved.

1. Ex-Post Moral Hazard

It occurs after protection, insurance, or guarantees are in place. Individuals or organizations may change their behavior because they feel shielded from potential negative outcomes.

Once people perceive themselves as “covered,” they might act less cautiously. This can lead to negligence, overconsumption of services, or risky actions that they would otherwise avoid.

- Example: A homeowner might neglect installing smoke detectors or performing fire safety checks after purchasing fire insurance. Similarly, drivers might drive more recklessly once they have comprehensive car insurance.

- Impact: This form of moral hazard can increase costs for insurers, governments, and service providers, as more claims or damages occur than would have without coverage.

2. Ex-Ante Moral Hazard

It arises before an event occurs, when people or organizations anticipate external protection or rescue and behave more recklessly.

Unlike ex-post, this type involves preemptive risk-taking because the actor expects a safety net. It is common in financial markets and corporate decision-making.

- Example: Companies may engage in high-risk investments or speculative ventures expecting government bailouts during economic crises. Similarly, banks might grant loans to risky clients, assuming central banks or governments will intervene if problems arise.

- Impact: It can encourage systemic risk, creating vulnerabilities in financial systems or large-scale operations. Governments and regulators often implement policies to discourage such behavior.

3. Individual Moral Hazard

It focuses on personal behavior and decision-making when people do not face the full consequences of their actions.

Healthcare, insurance, and consumer behavior often exhibit this pattern, as individuals overuse resources, act carelessly, or neglect preventive measures when insulated from the cost of their actions.

- Example: A patient with fully covered healthcare might overuse medical services, request unnecessary tests, or avoid healthy habits because they do not bear direct costs. Similarly, a person with guaranteed returns on investments might take excessive financial risks.

- Impact: It can strain systems like healthcare or insurance, leading to higher premiums, reduced efficiency, or misallocation of resources.

4. Institutional Moral Hazard

It occurs when organizations, financial institutions, or governments engage in risky or reckless practices, expecting external support in case of failure.

Institutions, particularly large ones, may operate under the assumption that they are “too big to fail” or that the government or other organizations will step in during crises. This can result in overleveraging, risky lending, or mismanagement.

- Example: Large banks might approve risky loans, invest in volatile markets, or expand aggressively, knowing that central banks or governments may bail them out during crises. Similarly, state-owned enterprises may take unsustainable financial risks, anticipating government rescue.

- Impact: It can threaten entire financial systems, increase systemic risk, and force governments to use public funds to stabilize failing organizations.

Causes of Moral Hazard

Moral hazard occurs when individuals or institutions take on excessive risk because they do not fully bear the consequences of their actions. Key causes include:

- Asymmetric information: When one party has more information than another, it can lead to decisions that cannot be properly monitored or controlled.

- Lack of accountability: Individuals or organizations may act recklessly when something shields them from the consequences of their actions.

- Insurance and risk transfer: Transferring risk to another party can reduce incentives to act cautiously.

- Government bailouts or safety nets: The expectation of external assistance encourages riskier behavior.

- Misaligned incentives: When rewards or penalties do not reflect the true risk of actions, they encourage individuals to take risks.

- Poor monitoring or regulation: Inadequate oversight allows individuals or institutions to engage in riskier behavior without detection.

- Overconfidence and misjudgment: Underestimating risks or overestimating the ability to manage potential losses can lead to moral hazard.

Moral Hazard in Different Sectors

Moral hazard can manifest across various sectors where the decision-makers do not fully bear the consequences of risk-taking. Key sectors include:

1. Financial Sector

- Banks, investment firms, and insurers may take excessive risks when they expect bailouts or insurance coverage.

- Misaligned incentives and a lack of proper oversight often exacerbate risk-taking behavior.

2. Insurance Sector

- Policyholders may engage in riskier behavior once they are insured.

- Insurers face challenges in monitoring actions and controlling moral hazard through premiums and terms.

3. Healthcare Sector

- If insurance covers the costs, patients or healthcare providers may use medical services or treatments excessively.

- This can cause waste and increase total healthcare costs.

4. Government and Public Sector

- Public institutions or agencies make decisions without fully bearing the impact of failure, especially when they rely on public funds as safety nets.

- It arises when expectations of bailouts or subsidies influence policy or operational decisions.

5. Corporate Sector

- Executives may pursue high-risk strategies to achieve short-term gains if compensation is tied to performance, while shareholders or stakeholders absorb losses.

- Misalignment between management incentives and the company’s long-term health can create a moral hazard.

6. Energy and Environmental Sector

- Firms may neglect safety standards or environmental regulations if they believe governments or insurers will bear penalties or cleanup costs.

Moral Hazard in Economics

In economics, researchers study moral hazard under principal-agent theory:

- Principals (e.g., shareholders, insurers, lenders) rely on agents (e.g., managers, policyholders, borrowers) to act responsibly.

- Since agents’ actions are difficult to monitor, they may pursue self-interest at the principal’s expense.

This dynamic is crucial in labor markets, contracts, and corporate governance, highlighting how hidden behavior undermines efficiency.

Moral Hazard in Game Theory

Game theory models moral hazard as a strategic interaction:

- Bankers vs. regulators: If bankers expect bailouts, they gamble with depositor money.

- Nash equilibrium: When all actors assume safety nets, risk-taking becomes the dominant strategy.

Impact of Moral Hazard

Moral hazard has wide-ranging implications:

- Economic instability: Can fuel asset bubbles and crises.

- Higher costs: Insurers raise premiums, and lenders increase interest rates to cover risks.

- Inefficient resource allocation: Funds may flow into risky or wasteful activities.

- Reduced trust: Weakens credibility in financial institutions, contracts, and government programs.

- Burden on society: Taxpayers often bear the cost of corporate bailouts.

Real-Life Case Studies of Moral Hazard

- 2008 financial crisis: Risky mortgage lending and derivatives created a global meltdown, with governments rescuing banks.

- Eurozone debt crisis (2010s): Countries like Greece borrowed recklessly, expecting EU aid.

- COVID-19 pandemic bailouts: Subsidies to airlines and large corporations sparked debates about future risk-taking.

- Public healthcare systems: In some countries, free services led to overuse and resource strain.

Criticism of Moral Hazard

Not everyone agrees with the concept’s widespread application:

- Overemphasis on risk: Some risks drive innovation and progress.

- Blaming the victim: Individuals are sometimes unfairly blamed for systemic failures.

- Policy misuse: Governments may cite moral hazard to cut social benefits, even when benefits are justified.

Solutions to Moral Hazard

Organizations can address moral hazard by creating systems that better align risks and consequences with the actions of decision-makers. Key solutions include:

- Improved monitoring and oversight: Implementing stricter supervision, audits, and reporting mechanisms helps ensure responsible behavior.

- Aligning incentives: Structuring rewards and penalties so that individuals or organizations bear the consequences of their actions reduces risk-taking.

- Risk sharing: Sharing risk between parties ensures that no single party is completely insulated from the outcomes, encouraging prudent behavior.

- Contract design: Well-designed contracts, such as insurance policies with deductibles, co-payments, or performance-based clauses, can reduce moral hazard.

- Regulatory measures: Enforcing rules, standards, and compliance requirements can deter risky actions and protect stakeholders.

- Transparency and information disclosure: Ensuring that all parties have access to relevant information reduces asymmetric information, which is a key cause of moral hazard.

- Education and awareness: Raising awareness about the consequences of risky behavior and promoting ethical practices can help mitigate moral hazard.

Final Thoughts

Moral hazard is one of the most important concepts in economics and finance. It explains how protection from consequences can distort behavior, leading to excessive risk-taking, higher costs, and systemic instability. From insurance contracts to global financial crises, moral hazard shapes how people, businesses, and governments act when shielded from losses.

We can manage it through regulation, incentives, risk-sharing, and accountability, even though we cannot eliminate it. By doing so, societies can encourage responsible behavior, ensure financial stability, and foster long-term sustainable growth.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

Q1. How is moral hazard different from adverse selection?

Answer: Adverse selection occurs before a contract or agreement, when one party has hidden information that leads to a poor match (e.g., high-risk individuals buying insurance). After a contract is in place, a party acts differently because it does not face the consequences.

Q2. Can moral hazard occur in everyday life?

Answer: Yes, moral hazard is not limited to finance or economics. Everyday examples include borrowing items without care, relying on warranties to neglect maintenance, or overusing communal resources because personal cost is minimal.

Q3. How do insurers try to reduce moral hazard?

Answer: Insurers use tools like deductibles, co-payments, coverage limits, and policy monitoring to encourage responsible behavior and reduce reckless actions by policyholders.

Q4. How is moral hazard measured or assessed?

Answer: Economists and financial analysts assess moral hazard by analyzing behavioral changes after risk transfer, insurance coverage, or safety nets, often using statistical models, empirical studies, or scenario analysis.

Q5. Can moral hazard be predicted?

Answer: While not perfectly predictable, economists and risk analysts use models, historical data, and behavioral insights to identify situations where moral hazard is likely to arise.

Recommended Articles

We hope this comprehensive guide on Moral Hazard helped you understand its impact on economics, finance, and decision-making. Explore our related articles on: